As the impacts of climate change intensify and the 2050 deadlines for net-zero commitments draw closer, carbon markets are fast becoming a central pillar in global and national climate strategies. Across sectors and borders, a growing consensus has long emerged on the need to meet climate targets. While cutting emissions is the fastest pathway to achieving this, carbon projects offer the opportunity for several additional benefits in addition to climate change mitigation outcomes.

But what makes a carbon project work? How do these projects go from conceptualization to generating certified carbon credits that are traded and retired in global markets? From initial design and feasibility studies to activity implementation, monitoring, credit issuance, and sales, carbon projects follow a structured process governed by internationally recognized standards and crediting mechanisms. These processes are technical, require complex stakeholder engagement, and have long-term environmental and social impacts. In Canada, the conversation about carbon projects is gaining momentum as more companies invest and report their commitments to offset emissions through carbon projects within and outside the country. A clear understanding of the carbon credit project life cycle improves the transparency and credibility of these projects. This article offers a practical overview of the carbon project lifecycle, drawing insights from sample projects in Canada and other parts of the world.

What are carbon projects?

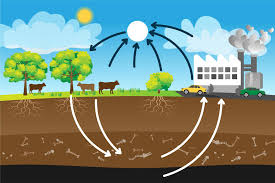

Also known as carbon offset or carbon sequestration projects, carbon projects refer to certified projects where activities are implemented to reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions. By reducing or removing emissions, these projects generate offsets, referred to as carbon credits. Carbon credits, measured in tonnes of CO2 removed or reduced, are sold in the international carbon market to governments, companies, or individuals seeking to offset their emissions or support climate change mitigation efforts. The term “carbon project” is more generic, encompassing mitigation activities that occur in all sectors, including those that avoid or reduce emissions, as well as those that remove emissions. However, carbon sequestration projects focus on removing or capturing emissions from the atmosphere. These projects are broadly categorized as geologic sequestration tailored to industries, utilizing innovative technologies to capture and store carbon emissions and terrestrial sequestration involving carbon removal through the natural process of photosynthesis in plants (trees, crops, and phytoplankton) using oceans and soils as carbon sinks (storage).

Carbon projects are implemented across various sectors and ecosystems, including energy, transportation, waste management, agriculture, and other land-use sectors. These projects engage in activities such as funding the use of clean cooking stoves to reduce deforestation, investing in renewable energy sources such as solar-powered electricity supply, and supporting the implementation of sustainable agricultural land management practices. Carbon projects that support the use of clean cooking stoves and transitioning to renewable energy sources help reduce or avoid emissions that would otherwise occur from the use of fossil fuels. Agriculture and other land use-related project activities, such as planting trees, support the removal of emitted CO2 through carbon sequestration. In both cases, the likelihood of reversing efforts to avoid or remove emissions exists. However, the nature of agriculture and other land-use-related project activities increases the chances of reversing removed emissions. This possibility of reversal is technically referred to as non-permanence, meaning the risk that emissions reduced or removed through project activities would be reversed over a long period. The following are key elements required by carbon projects across sectors. These elements are either factored into specific stages or the entire project life cycle.

- Baseline or business-as-usual scenario defines what existed before the carbon project. It is assessed and documented before the project implementation begins.

- Project scenario defines what is expected to occur regarding climate mitigation within the project context.

- Approval, such as Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), ensures that project participants or communities voluntarily decide to participate in the project before its commencement based on sufficient information. In the Clean Development Mechanism, participating parties (countries) are required to submit a Letter of Authority issued by the Designated National Authority.

- Additionality, which is proof that mitigation efforts would only occur with incentives from the issuance and sale of carbon credits.

- Benefit sharing of project incentives, which clearly defines the expected project benefits and how these benefits would be distributed among actors.

- Leakage assessment of what could happen outside the project area resulting from ongoing mitigation activities. An example of leakage is if participants in a forest conservation project engage in logging outside the project area.

- Permanence, which defines how long-lasting results from the mitigation activities can be sustained even after the project crediting period (project lifespan for generating carbon credits for carbon markets) ends.

While financiers of carbon projects often originate from developed countries, it is more common for project implementation to occur in developing countries, where over 90% of carbon credits were generated between 2020 and 2022. The case in Canada, however, is slightly different, as approximately 50% of carbon credits purchased by Canadian companies are generated in North America, an indication of a ‘regional allegiance. Carbon credit investments by Canadian financial service providers and software companies in 2021 increased significantly, doubling the investments made in 2020. The over 80% jump in prices of carbon credits, resulting from increased corporate commitment to climate neutrality in 2021, may have contributed to the surge in investments by Canadian companies. However, 2022 recorded a sharp and more than twofold decline in investments. There are currently over 60 carbon projects in different lifecycle phases and across various sectors in Canada. Key actors relevant to carbon projects include project developers, on-the-ground project implementers such as Indigenous communities, project proponents, third-party auditors or Verification and Validation Bodies (VVBs), standard developers and certifiers, national authorities, financiers, technical consultants, and buyers of carbon credits. These actors perform key project functions in different phases of the project life cycle.

Carbon project life cycle

The carbon project life cycle refers to the various phases through which climate mitigation activities are transformed into tradable carbon credits, enabling access to carbon finance. The project life cycle is sometimes condensed to include concept, project implementation, credits and certification, or design, issuance, and retirement phases. This approach fails to highlight the importance of every phase, spanning from project conceptualization and development to registration and validation, implementation, monitoring, reporting, verification, and the sale of carbon credits. Carbon program registries, which serve as central repositories for projects, provide relevant information about listed projects, including their life cycle phase, specifying whether they are under development, validated, registered, undergoing verification, or withdrawn, as applicable.

- Project development: The design and development of a carbon project requires a considerable investment of time, technical expertise, and financial commitment. A typical project design and development phase may last more than two years, requiring an investment of over US$500,000, primarily in field studies and the engagement of technical consultants. However, this cost is influenced mainly by project type, scale, and location. The pipeline listing (before validation, registration, or issuance of carbon credits) of a project on a carbon program registry is also an essential cost incurred in the development phase, costing between US$1,000 and US$1,500 for projects listed on the Verra registry. Project design and development is the first phase in the project life cycle and involves scoping, conceptualization, feasibility studies for site and environmental impact assessment, initial consultations and formation of partnerships. It also includes stakeholder mapping, extensive consultations, signing contracts, and developing the project governance structure. This stage requires establishing the project’s baseline before activities commence, selecting suitable standards and methodologies for project design, and quantifying the carbon offsets generated. It is recommended that the stage be process-focused, flexible, and adaptive, with documentation of relevant reports and collaboration between key stakeholders. An essential documentation outcome of this stage is the Project Design Document (PDD), which outlines the project’s objective and activities to be implemented, project location, risk assessment, stakeholders, and estimated emissions to be avoided or removed throughout the project’s lifetime. The Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of participating communities should also be obtained at this stage to foster community representation and inclusiveness throughout the design and implementation process. The project developer coordinates this stage. The Nature Conservancy Canada (NCC), Bank of Montreal, Westport Innovations, and Cree First Nation of Waswanipi are examples of project developers for Canada-based carbon projects. The Carbon Offset Aggregation Cooperative’s reducing GHG Emissions from industrial vehicles and mobile machinery carbon project is an example of a pipeline-listed project under development for the issuance of carbon credits in Canada’s transportation sector. While the success of a carbon project begins in this phase, project developers face challenges associated with the initial cost investment and the rigour required to frame the project appropriately. For indigenous communities, the risk of exclusion, which may lead to project failure, is common. In the development phase, projects cannot claim against emissions reduction or avoidance.

- Project validation and registration: Under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), projects are validated by the Designated Operational Entity (DOE) or third-party certifier after the project participants have submitted a Letter of Approval issued by their Designated National Authority. The letter of approval must indicate that the participating countries have ratified the Kyoto Protocol, are participating voluntarily and that the project activity to be implemented contributes to sustainable development. The validation phase assesses planned project activities to ensure they meet established standards and procedures. The importance of this phase lies in its role in ensuring the credibility of carbon offsets. Under the CDM, validated projects must be submitted by third-party certifiers to the CDM’s executive board. The executive board vets the submitted project and formally accepts it as a CDM project activity. This is referred to as project registration. It is only after successful registration that projects qualify for the verification of carbon credits. In voluntary market carbon projects, validation is conducted similarly by a third-party auditor known as the Validation and Verification Body (VVB). VVBs are responsible for ensuring the accuracy of data and calculations submitted by the project developers in the project development phase. They also ensure the compliance of project design with selected standards and methodologies before the project is registered and listed as an operational carbon project that can issue carbon credits. At this stage, projects can claim credits for emissions reduction or avoidance; however, they still require verification of the generated carbon credits to make them tradable. Different crediting programs charge varying fees for validation and registration based on specific standards and project types. For instance, on average, Verra charges approximately US$5,000 for project validation and registration, while the American Carbon Registry (ACR) charges US$2,500 for project validation. The Anew Quinte Forestry Project, developed by Anew Carbon Development, LLC, is an example of a Canadian carbon project in the agricultural sector that has been validated and registered under the American Carbon Registry.

- Project Implementation: This phase is driven by project implementers, including communities, Indigenous peoples, and NGOs, who coordinate to carry out planned activities aimed at reducing or removing carbon emissions. These activities differ across sectors. Projects in the energy sector include activities such as the installation of solar panels and the distribution of clean cooking stoves aimed at reducing dependence on fossil fuels and firewood. Other project activities include supporting regenerative agriculture, planned rotation grazing, afforestation, reforestation, and the conservation of coastal areas, such as mangroves, salt marshes, and peatlands, as in blue carbon projects. There are also carbon projects that involve technologies to capture methane emissions from rice fields and livestock. The project implementation phase is capital-intensive and could cost as much as US$10,000,000 for renewable energy projects. This includes the costs of technologies, project staff salaries, training, procurement, and distribution of project materials, such as tree seedlings, in afforestation and reforestation projects. To cover these costs, project developers typically secure upfront financing from investors or partners, while long-term funding is sustained through the sale of verified carbon credits. Upfront investment can be structured as loans, equity, or forward purchase agreements, where buyers commit to purchasing future credits at a discounted rate, thereby mitigating the risk associated with early development. This financing model has been applied in several projects in Canada. The Great Bear Rainforest Carbon Project in British Columbia, for example, utilized carbon credit presales to support First Nations communities and conservation groups in financing early forest conservation activities. This approach to funding suggests that carbon finance is not merely a revenue stream but can also be structured as a foundational tool to launch and sustain nature-based climate solutions through carbon projects.

- Ongoing Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting: The monitoring, evaluation, and reporting phase begins with the implementation of project activities. However, it remains ongoing throughout the project’s lifespan as a requirement for the issuance of carbon credits. As part of monitoring, project actors establish systems to collect data and document the project’s performance and contribution to emissions avoidance or removal through the activities implemented. Beyond monitoring, these reports are evaluated to assess the project’s impact on emissions reduction and removal, as well as any project-related social and other environmental impacts in the project area against its baseline (before the project scenario). Each evaluation report serves as the baseline for subsequent evaluations. The selected standards and methodology provide guidelines for this phase. Depending on the project type, monitoring may be conducted every week as the process is more continuous. For example, in carbon projects implemented in extensive livestock systems, data on livestock movement is collected every week. Evaluation, on the other hand, is conducted periodically and may be done on a biannual or annual basis. In carbon sequestration projects, evaluation involves analyzing soil samples, data from satellite imagery, and measuring tree dimensions to quantify biomass and assess changes in carbon stocks against the project baseline. The project implementers, developers and technical consultants work together to ensure the success of this phase. Costs vary depending on the project and its location, but could amount to US$70,000, including US$60,000 for engaging technical consultants and US$10,000 for field assessments. Among other principles, it is recommended that this phase, as well as the subsequent verification phase, must be technically sound, transparent, consistent, cost-effective, and objective. These principles are essential because they increase the project’s credibility among stakeholders.

- Verification and Issuance: During the verification phase, third-party auditors (Validation/Verification Bodies) review monitoring and evaluation reports submitted by project developers, assessing the implementation of project activities and progress toward emissions reduction or removal. This is required to verify the issuance of carbon credits by the project formally. The relevant crediting program accredits the VVBs in accordance with the requirements of specific sectoral scopes, enabling them to carry out this function. They are required to undergo periodic training to strengthen their performance and integrity of the projects they audit. The VVB assesses whether the project activities have been implemented in accordance with the approved methodology and whether the reported emissions reductions or removals are genuine, measurable, additional, and permanent. This process is typically conducted every 1 to 5 years, depending on the project type, crediting standard, and market preferences. Following the commencement of the verification process, if the VVB identifies discrepancies or non-conformities, it provides the project developer with a chance to respond and rectify the issues before the verification report is finalized. Once the VVB confirms compliance, the verification report is submitted to the crediting program operator (e.g., Verra or Gold Standard), and carbon credits are officially issued. While issued credits can be sold (before or after verification), a final project life cycle phase is required for the issued credits to count towards net emissions. Verification costs vary from one crediting program to another, sometimes amounting to US$50,000 per cycle, depending on the project’s size, complexity, and scope. Additional administrative issuance fees apply. For example, Verra charges US$0.10 per Verified Carbon Unit (VCU) for the first 15,000 tonnes issued annually and US$0.20 per excess tonne of net emissions reported by a project. Each verified issuance is recorded in the public registry of the crediting program. The identity of the VVB, the volume of credits issued, the amount reserved in the buffer pool (to mitigate reversal risks) and the project documents are made publicly available to enhance transparency and traceability.

- Retirement: Double counting occurs when more than one entity lays claim to the emissions reduction or removal by a carbon project. For instance, if a project host country and a private buyer claim the project’s net emissions separately. High-quality and credible carbon credits must avoid double-counting, as it is not possible for a specific activity to contribute to net emissions twice within the same period. While this challenge is more likely to occur in country-level carbon trading or when crediting programs issue the same credit to different entities, the retirement of carbon credits issued as the final phase in each project verification cycle addresses this problem. Through a transparent, documented, and certified process, the retirement phase requires that the carbon credits after sales are transferred from the project developer’s account to a retirement account. The information on retirement should be publicly verifiable on the crediting program’s registry, as it finalizes the process, makes the net emissions contributions permanent and ensures that no other entity lays claims to the carbon credits.

Carbon projects are complex systems that connect scientific methodologies, stakeholder engagement, investments, and governance. From design and baseline assessments to monitoring, verification, and final credit retirement, each phase plays a critical role in ensuring the credibility of carbon credits. In Canada and around the world, the demand for high-quality carbon projects is increasing as companies, governments, and individuals seek effective tools to meet their climate targets. However, the success of these projects depends on adherence to rigorous standards and practices throughout the project life cycle. Incorporating principles such as Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), environmental and social safeguards, and sound monitoring frameworks helps strengthen both the legitimacy and longevity of project outcomes.

More Details about Carbon Markets can be found here:

Nature Conservancy Canada: (https://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/what-we-do/nature-and-climate/frequently-asked-questions.html#:~:text= NCC’s%20carbon%20offsets%20are%20sold,offsets%20on%20a%20voluntary%20basis.)

(https://www.leafcoalition.org/; https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/firms-including-amazon-buy-180-million-carbon-credits-namesake-rainforest-2024-09-24/);

References

ACR (2024). ACR Fee Schedule. https://acrcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ACR-Fee-Schedule-February-2024.pdf.

Berkeley Public Policy (2025). Voluntary Registry Offsets Database. https://gspp.berkeley.edu/berkeley-carbon-trading-project/offsets-database.

Carbon Direct (n.d.). The carbon credit lifecycle explained. https://www.carbon-direct.com/insights/the-carbon-credit-lifecycle-explained. Accessed on 20.06.2025.

Climate Partner (n.d). What is the life cycle of a climate project? https://www.climatepartner.com/en/project-life-cycle. Accessed on 20.06.2025.

CPA, IFAC & ISF (2024). Global & Canadian Use of Voluntary Carbon Credits and the Related Financial Accounting and Disclosure Considerations. https://smith.queensu.ca/centres/isf/pdfs/projects/voluntary-carbon-markets2.pdf.

Evans, L., Tyrrell, P., Brehony, P., Muiyuro, R., Timanywa, K., Odire, E., Kaelo, D., Warigia, G., Langan, C., Ender, C., Anderson, L. B., Ayuo, J., Mbataru, J., Wairimu, E., Nelson, F., Gathu, C. (2025) A Guide to Carbon for Conservancies. Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association. kwcakenya.com/download/a-guide-to-carbon-projects-for-conservancies/?wpdmdl=12705&refresh=68555e7149d331750425201.

FAO (n.d.). Carbon Finance Possibilities for Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use Projects in a Smallholder Context. i1632e03.Pdf.

FG Capital Advisors (n.d.). How Much Do Carbon Projects Cost? https://www.fgcapitaladvisors.com/how-much-do-carbon-projects-cost. Accessed on 22.06.2025.

GIZ (n.d.). Introduction to Carbon Credit Projects and its Applicability for Cocoa Agroforestry in Viet Nam. https://www.giz.de/en/downloads_els/240611_Deliverable%204_Guidance%20Docs_v3_FINAL_EN.pdf.

Global Carbon Fund (2024). Carbon Prices and Voluntary Carbon Markets Faced Major Declines in 2023, What’s Next for 2024? https://globalcarbonfund.com/carbon-news/carbon-prices-and-voluntary-carbon-markets-faced-major-declines-in-2023-whats-next-for-2024/. Accessed on 19.06.2025.

Government of Canada (n.d.). Great Bear Rainforest: a blueprint for success. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/nature-legacy/campfire-stories/great-bear-rainforest.html. Accessed on 19.06.2025.

The New Climate (2025). Carbon Markets: What are they, and how do they work? https://thenewclimate.ca/carbon-markets-what-are-they-and-how-do-they-work/. Accessed on 19.06.2025.

Twyman, C., Smith, T. & Arnall, A. (2015). What is carbon? Conceptualising carbon and capabilities in the context of community sequestration projects in the global South. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 6. 10.1002/wcc.367. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282404279_ What_is_carbon_Conceptualising_carbon_and_capabilities_in_the_context_of_ community_sequestration_projects_in_the_global_South/citation/download.

UNFCCC (n.d.). CDM Project Life Cycle. https://cdm.unfccc.int/Projects/diagram.html.

Verra (2024). Verra Program Fee Schedule. https://verra.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Verra-Program-Fee-Schedule-v1.0.pdf.

Verra (n.d.). VCS Program Details. https://verra.org/programs/verified-carbon-standard/vcs-program-details/#validation-and-verification.

Whiting, T. (2023). What’s the difference between ex-post, ex-ante, and pre-purchase carbon credits? https://lune.co/blog/whats-the-difference-between-expost-exante-and-prepurchase-carbon-credits. Accessed on 22/06/2025.

Whiting, T. (2023). What is double-counting in carbon offsetting? And why is it important? https://lune.co/blog/what-is-double-counting-in-carbon-offsetting-and-why-is-it-important. Accessed on 23/06/2025.